Body Corporate’s Duty to Repair and Liability

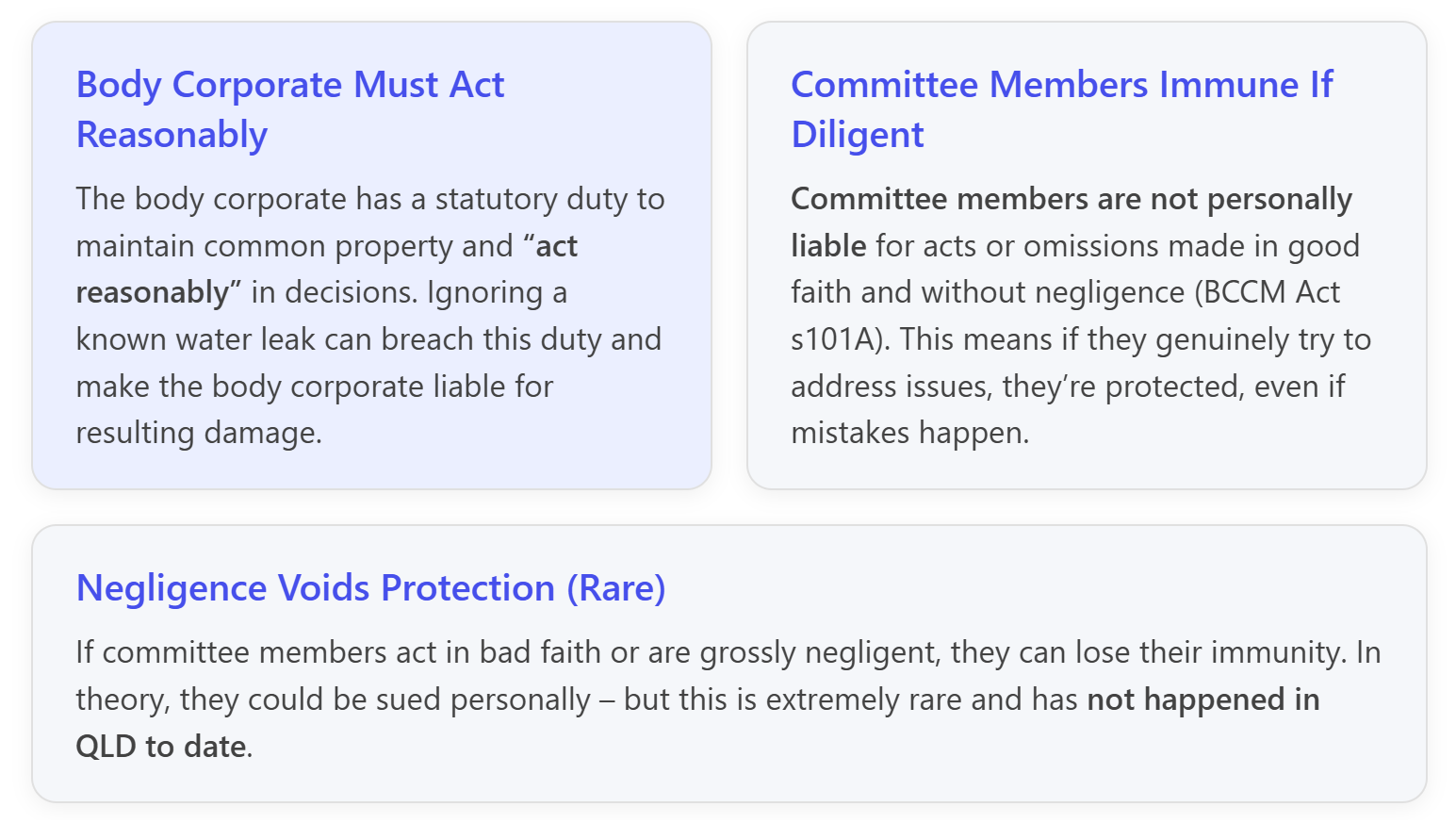

Under the Body Corporate and Community Management Act 1997 (QLD), the body corporate (all owners collectively) must maintain common property in good condition and “ensure the common property... is administered for the benefit of owners”. The committee, acting on behalf of the body corporate, is expected to make reasonable decisions about repairs.

Water Ingress Example: If an expert report warns of water ingress (e.g. a leaking roof or exterior wall) that could cause damage, the body corporate is expected to address the issue within a reasonable time. Failing to do so can be seen as acting unreasonably under BCCM Act Section 94.

Liability for Damage: Should the body corporate ignore the problem and, say, an owner’s unit is damaged by the leak, the body corporate (as an entity) can be held liable for the repairs. An affected owner can lodge a dispute seeking orders for the body corporate to fix the leak and compensate for losses. The law views this as the body corporate’s responsibility, since it failed its maintenance duty.

Who Pays? Any compensation or repair costs ordered would typically be paid from the body corporate’s funds or insurance, not from committee members personally. All owners effectively share the cost via levies or insurance premiums. (If the body corporate has building insurance, it may cover resultant damage from leaks – although deliberate neglect might complicate insurance claims.)

In short, the body corporate itself bears the primary liability for not fixing common property issues. Queensland strata law provides mechanisms to enforce this (through the Commissioner’s Office or QCAT), ensuring common property is maintained. The focus is on the corporation, not individual volunteers.

Committee Members’ Legal Protection

Committee members are the elected owners who make day-to-day decisions. Given they’re usually volunteers, the law gives them strong protections:

Immunity (BCCM Act Section 101A): A committee member “is not civilly liable” for anything done (or not done) “in good faith and without negligence” in performing their role. This is a crucial shield. If the committee tried to handle the water ingress situation in good faith – e.g., discussed it, sought quotes, maybe delayed a bit but not recklessly – they would be protected from personal lawsuits. Any legal action would be against the body corporate as a whole, not the individual members.

What counts as Good Faith? It means the member honestly believed they were doing the right thing for the scheme. As long as they aren’t acting with malice, self-interest, or willful disregard, this condition is met.

What is “Without Negligence”? It means they act with the level of care and diligence expected of a reasonable person in that role. You don’t have to be perfect, just not grossly careless. Mistakes or poor decisions can happen, but if you at least exercised some care (e.g., considered the issue, sought advice), you’re likely within the safe zone.

Scope of Protection: This immunity covers acts and omissions – meaning failing to act is also protected if it wasn’t negligent or in bad faith. It covers committee decisions like deferring a repair, as long as there was a reasonable basis (for example, waiting for a second report or not having funds immediately). It also specifically protects against legal liability; importantly, the BCCM Act does state an exception that it “does not affect liability for defamation” (so committee members could still be personally liable if they, say, libel someone – but that’s unrelated to maintenance issues).

Body Corporate vs. Committee Member: A suit for failing to maintain common property would normally name the body corporate. Thanks to s101A, a committee member can ask a court to throw out any personal claim against them by citing this immunity, provided they acted in good faith and not negligently.

In essence, Queensland law wants committee members to serve without fear. If you’re doing your best (even if the outcome isn’t perfect), your personal assets aren’t at risk. The legal liability stays with the body corporate.

When Personal Liability Could Apply (Negligence or Bad Faith)

The protection is broad, but not absolute. If a committee member acts in bad faith or is negligent, they lose the statutory immunity. What might that look like in a water-ingress scenario?

Bad Faith: Perhaps a committee member ignores a leak because it’s not affecting their own unit or out of spite toward the complaining owner. That’s acting in self-interest or malice, not in the scheme’s best interest. It violates the committee Code of Conduct (Act, Schedule 1A) which requires acting honestly, fairly, and in the body corporate’s interest. A deliberate decision to “do nothing” in spite of known risk could be bad faith.

Negligence (Gross Carelessness): Say an engineer’s report says “urgent works required to avoid major damage,” and the committee just... files it away and never discusses it or informs owners. This inaction, with obvious foreseeable damage, could be seen as gross negligence. The committee didn’t exercise due care any reasonable person would.

If an owner incurs loss due to this kind of extreme committee failure, they might attempt to hold members personally accountable. For example, an owner could potentially sue committee members for negligence, arguing their unreasonable inaction caused the owner financial harm.

However, in practice such cases are exceedingly rare. To date, no reported Queensland case has held an individual committee member personally liable for inaction on maintenance. There are a few reasons:

Legal Hurdles: The owner would have to prove the committee member’s personal duty and negligence, overcoming the s101A immunity by showing lack of good faith or presence of negligence. That’s a high bar. As long as the committee member can point to any rational process (even if the decision was “wrong”), courts tend to defer. One legal commentary notes it’s “almost impossible” to deem a decision not “reasonably held” if there was some basis for it.

Volunteer Consideration: Courts recognize committee members are not professional managers. Public policy is sympathetic to volunteers. A “mere” delay or oversight typically won’t be punished; it usually takes willful or grossly careless conduct to even consider personal liability.

Collective Nature: Often it’s a committee decision not just one person. It may be hard to pin blame on one member. And you generally sue the committee as representatives of the body corp, not as individuals.

Alternative Remedies: Owners have easier ways to resolve the issue (order against body corporate, emergency repairs and recover costs, etc.) than suing individuals. If the body corporate fixes the leak after a formal order, the matter is solved without targeting committee members personally.

Example – Attempted Personal Lawsuit: While rare, there have been attempts. For instance, a committee chair in QLD once personally okayed an owner’s request to replace a fence, but later the committee objected and made the owner remove it, causing the owner expense. The owner then sued the chairperson personally for those costs. This suggests that if committee members act outside their authority or improperly, they can be dragged into personal litigation. (Outcome of that case aside, it’s a warning: stick to proper process and authority to stay protected.)

Consequences if Liability Arises: If a court did find a committee member liable, that member could be ordered to pay damages out of pocket. They could also face removal from the committee. The BCCM Act’s code of conduct enforcement allows the body corporate to vote out a member who seriously breaches their duties. In an extreme scenario, insurance might not cover a truly reckless act (more on insurance next). Again, this is hypothetical — in virtually all real cases, the resolution is at the body corporate level, not personal.

Best Practices to Avoid Personal Liability

For committee members, the goal is to never even approach that “negligent” threshold. Here’s how:

Act Promptly and Document Efforts: The moment a water ingress issue is reported, put it on the committee meeting agenda or initiate an email discussion. Document that the committee acknowledges the issue and is taking steps (e.g., “We have called a plumber for quotes,” or “We need an extraordinary general meeting for funds”). This paper trail shows good faith effort.

Get Expert Advice: If a report is confusing or the solution is unclear, seek a second opinion or consult a strata manager or building consultant. Relying on expert advice can defend your actions. If an expert advises a certain fix and you follow it (even if it later proves inadequate), that’s acting with due care.

Communicate with Owners: Keep affected owners informed: “We are aware of the leak and are doing X, Y, Z.” Lack of communication often leads to mistrust and escalations. Transparency demonstrates you’re not ignoring the issue.

Prioritize Safety and Mitigate Damage: If a leak is actively causing damage, take interim measures (tarps, buckets, shutting off water) while awaiting a permanent fix. Also, if an owner requests approval to do urgent repairs themselves to stop damage, consider granting it (the Act allows owners to intervene in an emergency and later get reimbursement from the body corp).

Follow the Code of Conduct: Always act honestly, fairly, and in the best interest of all owners. Disclose any conflict (e.g., the leak is in your unit – still act objectively). Don’t let personal issues or apathy interfere with duties.

Use General Meetings for Big Decisions: If the repair cost is high or contentious, call an extraordinary general meeting so all owners can vote. This spreads the responsibility and ensures you have a sanctioned mandate. It also protects the committee since you’re implementing a direct decision of the body corporate.

Obtain Office Bearers Insurance: Nearly all strata insurance packages offer Office Bearers Liability coverage. This insurance covers committee members against legal claims arising from their decisions (typically excluding dishonest or fraudulent acts). It will pay for legal defense and any settlement/judgment up to the policy limit. Ensuring your scheme has this cover is critical – it provides peace of mind that if someone does sue you personally, you’re not on your own. (Most well-run bodies corporate have this; if yours doesn’t, raise it with your insurance broker or strata manager. It’s usually inexpensive.)

Don’t Overstep Authority: Individual committee members should avoid making unilateral decisions that bind the body corporate. Always get proper committee or owner approval as required. Acting rogue (like the fence example) removes the safety net because you’re no longer “performing your committee role” – you’re acting outside it.

By following these practices, committee members will nearly always be viewed as acting in good faith and with appropriate care – thus enjoying full protection from personal liability.

Conclusion: In a case of unaddressed water ingress, the body corporate can indeed be held accountable to fix the issue and pay for damages. Committee members, however, are generally shielded from personal liability by law, unless they behave in a way that is negligent or not in good faith. The legal framework (BCCM Act sections 94, 101A, and the Committee Code of Conduct) ensures that the focus is on correcting the problem rather than penalizing individual volunteers. Queensland has mechanisms to remove or replace dysfunctional committees, but suing committee members personally is practically unheard of except in extraordinary situations.

For committee members worried about this scenario: act promptly, document everything, and use the resources and protections available to you. This way, you fulfill your duties, the issue gets resolved, and the question of personal liability never needs to be tested. In summary, do the right thing and you’ll be fine – the law has your back.